Explained:India Defeated China in 1967

Ramachandran

The Sino-India war of 1962 resulted in China redrawing the border as the Line of Actual Control in its own favour,but in 1967 the second Sino-India war of 1967 saw India push China back.The clash between India and China in 1967 is often remembered as the last shot fired on the India-China border.

That clash in Sikkim, where India got the better of China just five years after defeat in the 1962 war, saw more than 80 Indian soldiers killed while estimates say 400 Chinese soldiers may have been killed.

In 1967, India fought a battle against China to restore its self-respect and protect its land and won. The 1967 battles of Nathu La and Cho La pass changed the Indo-China political dynamics forever. But no one speaks about this resounding victory.

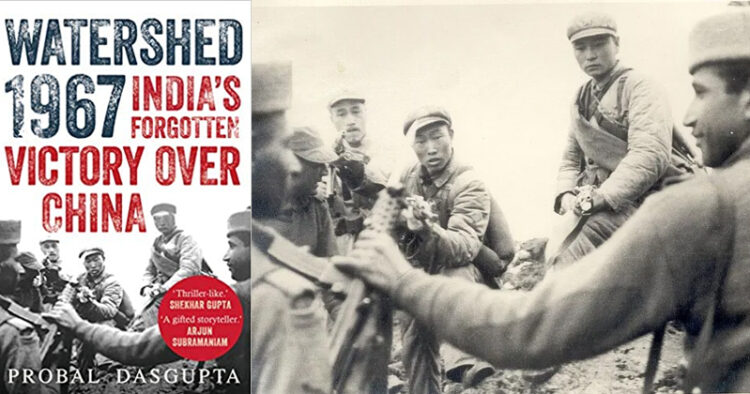

In his book, ‘Watershed 1967: India’s forgotten victory over China’, army veteran Probal DasGupta explores the mystery.

“When you look at 1971, China didn’t interfere in the India-Pakistan war. Not many have asked that question as to why, but there are many reasons why 1967 is an important yet underrated reason why China did not go down the Siliguri corridor and cut India out. Thereafter, at various stand-offs, whether it is Daulat Beg Oldi or Doklam in 2017, India has always used that template and obtained a dominating position in stand-offs against China.”,he points out. “I think that has set the template and has also ensured, what I’ve maintained – that peace is obtained when you achieve parity. Hence, there was a parity that was obtained in 1967, which got back India’s pride and was also responsible in conveying to China that they’re militarily a bigger power and that they could not overrun India anymore,” adds Das Gupta.

Relations between India and China were already tense in 1967 but matters came to a head in August 1967. Irked by India’s decision to erect iron pickets along the border from NathuLa to Sebu La, the Chinese began to heckle Indian soldiers. What followed soon was a full blown clash with the Chinese attempting to wrest control over the Nathu La pass from India. A daring decision by the commanding officer, Lt General Sagat Singh stopped their plans from succeeding.

“As India was going up against Pakistan on the Western front, Chinese troops had amassed across the border near Sikkim, and that was the time when it was expected that Indian troops would pull back from Nathu-La. But General Sagat refused to do so because that would give the Chinese easy access to the Siliguri corridor down the Sikkim axis. Therefore, he disagreed with his superiors and stuck to his decision,” says Das Gupta.

Had General Sagat Singh not stood his ground, Chinese troops stationed at Nathu La would have captured the pass. This would give them easy access to the Siliguri corridor during the 1971 war. The outcome of the 1971 India-Pakistan could have then been very different.

“Psychologically, the political leadership was rattled and was even quite demoralised in 1962 as far as China was concerned. We had achieved some success against Pakistan in 1965. However, the overall attitude towards China was still very much different and defensive. Going against the grain of leadership was extremely creditable of General Sagat at that point of time,” Das Gupta records.

In October 1967, another clash at Cho La ended in a similar manner as the one in Nathu La. Gorkhas and Grenadier troops of Indian Army demolished Chinese PLA forces in these battles. At least 88 Indian soldiers and over 340 Chinese troops lost their life in the battles and over a thousand were injured.

DasGupta believes that it was the right kind of political and military leadership of officers like General Sam Manekshaw and General Sagat that made the difference in the battles of 1967.

Probal DasGupta attributes multiple reasons why the battles of 1967 were forgotten.

“It was an era when India had suffered reverses a few years before that. Five years before that, in the 1962 India-China war, India had suffered a heavy setback. So, when this happened, it wasn’t covered as much in the media and people couldn’t really come to terms with what had happened there.”

Secondly, it was also because India and China had kind of not wanted to play it up as much. So, I think tacitly it was agreed to not play it up in the international fora. Thirdly, the most important reason was in 1971 when India had registered a resounding victory which whitewashed a lot of things that had happened in the past.”

Pointing that history shapes a narrative, DasGupta said, “The history of 1962 was written by Brigadier John Dalvi, who was the commander of the 7th Brigade, one of the first Indian brigades to be defeated by Chinese forces. Brigadier Dalvi was taken prisoner and he was kept in China for some time. After he came back, he wrote a book. It was bitter and explosive, but we banned the book.”

“Thereafter, Neville Maxwell wrote a book on India and China; it was sympathetic to China. What happened with that is when Henry Kissinger went to China in 1970-71, he visited Beijing and he met Zhou Enlai, and Zhou Enlai gave him that book as a gift. Henry Kissinger’s drift on China and his entire anti-India narrative was based heavily from his learnings from the book, which he found to be extremely impressive. So this is what history does. History does shape a narrative,” he added.

If it is true that 1967 marked the last major fighting that saw casualties on both sides, it was not, however, the last incident of a shot being fired on the contested boundary.

That would happen eight years later, when a patrol of Assam Rifles jawans was ambushed by the Chinese at Tulung La in Arunachal Pradesh. Four were killed.

The Indian government maintained that the Chinese had crossed the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and ambushed the patrol on October 20, 1975. The Chinese denied this and blamed India for the incident.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing accused the patrol of crossing the LAC and firing at a Chinese post. The Ministry handed a protest note on October 22 to the Charge d’Affaires of the Indian embassy in Beijing describing China’s actions as “a self defence response”, according to a November 3 report in the French newspaper Le Monde.The report said India recovered their bodies a week later on October 28.

A U.S. State Department cable from 1975 noted India’s view that the “Chinese ambush was sprung 500 metres south of Tulung La” and took place on Indian territory. It quoted a senior Indian military intelligence officer as saying on November 5 the border there was very clear, marked by a distinctive shale cliff. He said China had moved up a company to the pass and detached a platoon which erected stone walls on India’s side of the pass, and from there fired several hundred rounds at the patrol. Four of the patrol had gone into a leading position, while two others, who escaped, had stayed behind. The officer said the patrol was routine and had been in the area several times before.

The cable noted that Tulung La was among the more remote passes in the region, a few dozen kilometres from Bum La and Tawang. It noted China had used the pass during the 1962 war as a channel to send its troops down to Bomdi La, to defeat the Indian resistance there to their offensive.

“Although the Chinese appear to be following their policy of enforcing the status quo with respect to the LAC pending negotiations,” the cable concluded, “they apparently still lay claim to Arunachal Pradesh down to the foothills”.

Bloodless clashes have erupted after 1967 with both sides quick to de-escalate friction to avert another war. In 1996 both sides agreed not to use firearms in the area.

Tensions rose again in 2017 when Beijing began building a road into Bhutan, an area New Delhi considers a buffer zone. In a tense stand-off, Indian and Chinese troops threw rocks at each other as a precursor to the current situation.

The 255km Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road that connects Leh to the Karakoram Pass runs almost parallel to the border separating Ladakh from China’s Xinjiang province. It runs alongside the Shyok River, a critical communication line close to the LAC. The road, which has been two decades in the making, would allow the rapid deployment of Indian troops to the disputed area and has become a flashpoint between the Asian giants.

Another point of contention is the China National Highway 219 (G219) connecting Xinjiang to Tibet. Originally built in 1957 and made of gravel, G219 was upgraded to asphalt in 2013. About 179km of the highway passes through the disputed Aksai Chin plateau.

What Happened now?

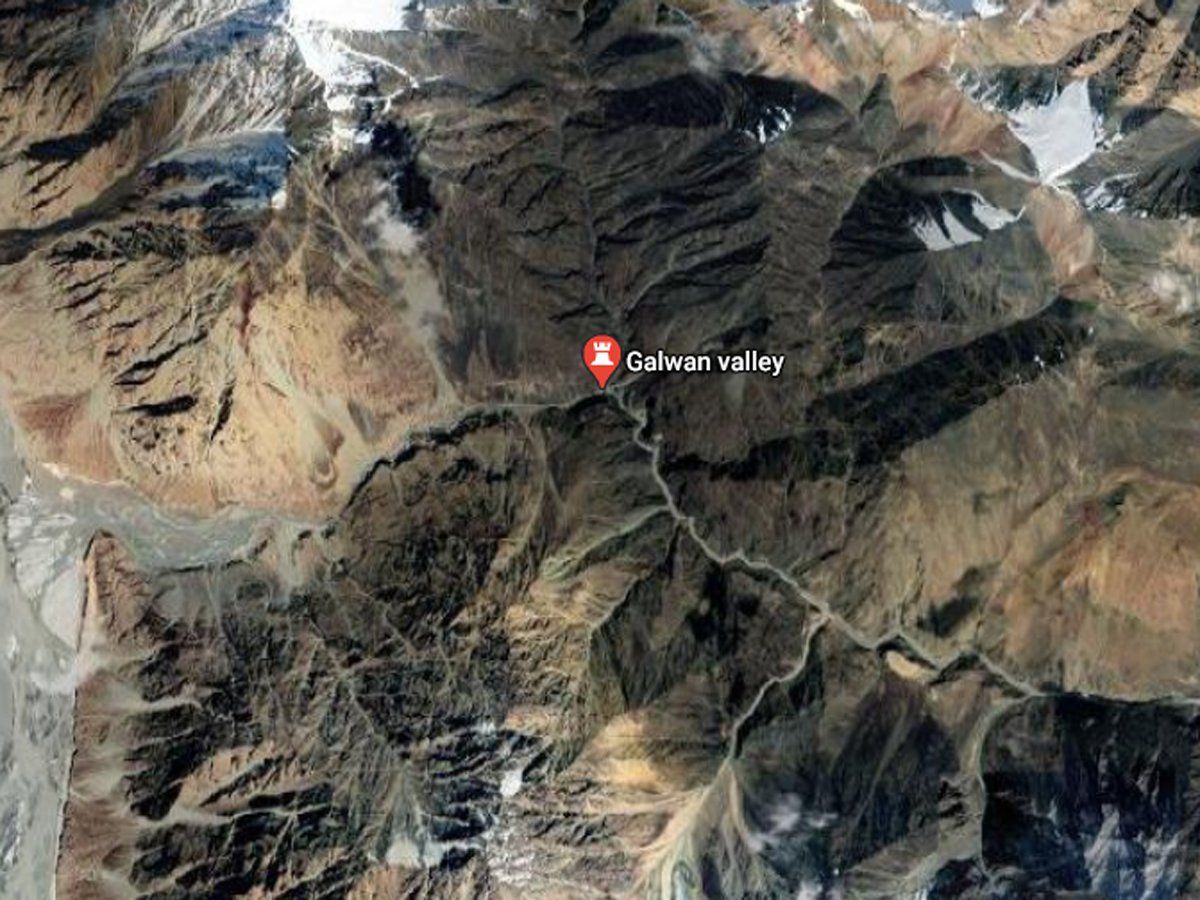

The fatal face-off took place in the moonlight on June 15, when soldiers from the Indian Army clashed with troops from the People’s Liberation Army close to Patrol Point 14 in the Galwan Valley of eastern Ladakh, more than 4,300 metres above sea level.

The Galwan River is the highest ridge line and overlooks the DSDBO road, posing a direct threat to the highway’s security. By controlling this area China can keep India’s claims on the Aksai Chin plateau in check. India claims China has recently begun amassing troops in the LAC and venturing deeper into the contested area.

China is also constructing the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to the west of Daulat Beg Oldie, in the critical Gilgit-Baltistan region where China abuts Pakistan and India.

The Galwan Valley contains some of the most treacherous terrain on Earth. Conditions are extreme. Steep slopes of almost 50 per cent are jagged and full of loose rocks. The landscape, altitude and lack of oxygen makes physical activity highly demanding. The slope where the clash occurred is shown in the following satellite image from the opposite angle.

India and China signed a series of border agreements in 1993, 1996 and 2005. The 1996 agreement sought to reduce aggression by banning firearms and explosives within 2km of the LAC. An exception is made for military exercises, which allows for limited range weapons.

As a result, when the Indian soldiers encountered Chinese troops on June 15 both sides attacked each other with bare fists and medieval-looking clubs spiked with nails and wrapped in barbed wire. A video that circulated online showed how some soldiers died in the fight, while others from falling into the icy river below.

The Galwan River flows from Aksai Chin towards Ladakh. Galwan Valley and the adjoining region experience freezing temperatures for much of the year. The forbidding conditions are arid and inhospitable.

The low atmospheric oxygen, low humidity, and strong ultraviolet radiation experienced at high altitudes can induce a number of pathophysiological phenomena, which can lead to disorders of the cardiovascular, respiratory, and ocular systems.

Military operations 4,000 metres above sea level represent complex challenges. Soldiers need to stop at different heights over several days to acclimatise to the altitude. Ascending too quickly can put even young and healthy soldiers at grave risk of acute altitude sickness, pulmonary oedema, and cerebral oedema.

Even after they acclimatise, the speed at which soldiers can move is compromised, as are the loads they can carry, and they need to consume additional calories to remain fit and healthy.

In addition to altitude challenges the temperature adds further stress to the soldiers’ well-being, with humans unable to withstand prolonged periods in temperatures above 50ºC or below -26ºC, which are common in the region.

The mildest form of altitude sickness, AMS is produced by a lack of oxygen and can affect anybody. Symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, irritability, dizziness and sleep disturbance, and can appear three to 24 hours after ascent. The incidence and severity vary with the initial altitude, rate of ascent, level of effort, and individual body conditions.

Above 4,000 metres, most people who have not gone through an acclimatisation process will lose 20 percent of their normal skills, which may persist after acclimatisation. At least half of all people without acclimatisation will experience some or all of the symptoms for several days. Height also affects a series of cognitive abilities, deficiencies in psychomotor performance, mental abilities or the ability to react quickly, Surveillance capacity, memory and logical reasoning are also affected.

Since 1949, China has been involved in 23 territorial disputes including sovereignty over Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. Most of the disputes have been resolved; six remain active.